Berlin Dada. The German Dadaists Of Berlin Club Dada Changed Modern Art. Their Work Still Influences Modern Artists.

DADA ARTISTS

DADA ART

DADA IN PRINT

Berlin Dada. The Effect of 20th Century German Dada.

CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE

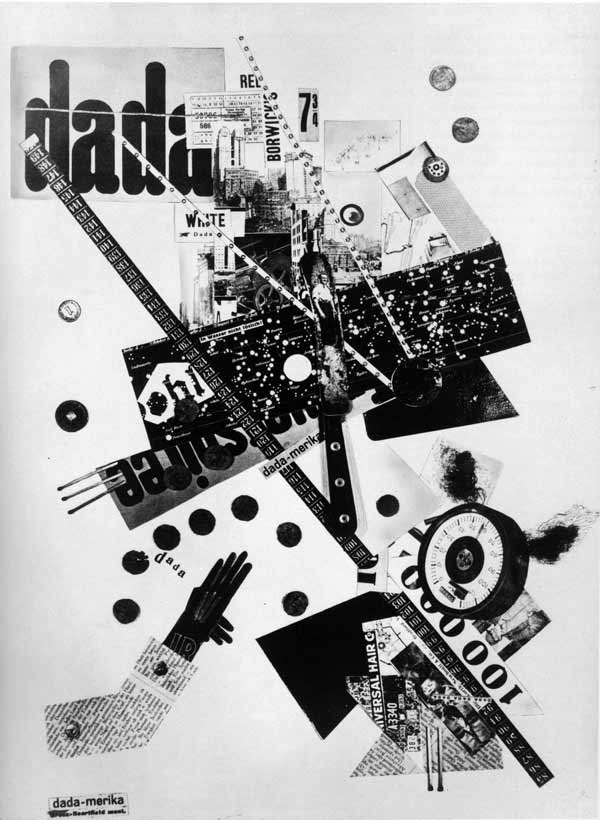

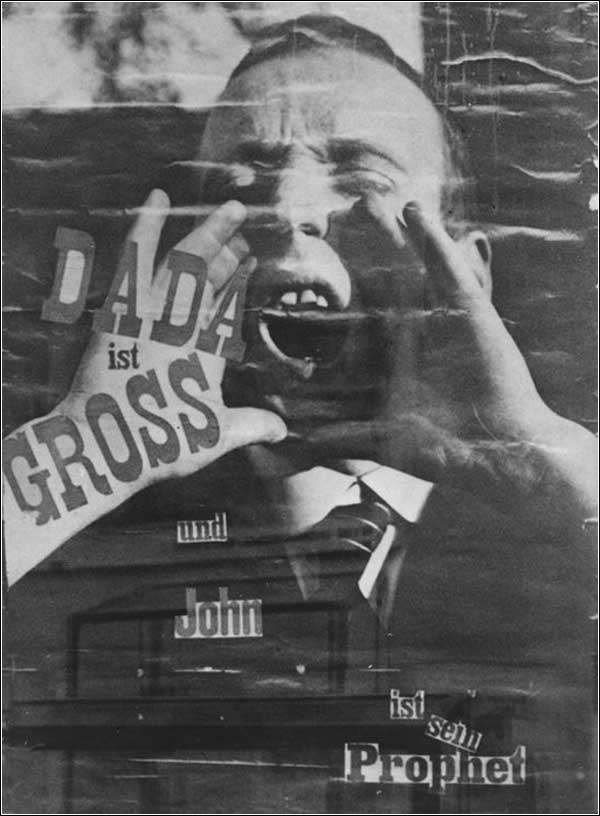

The groundbreaking typography reading "DADA ist GROSS und John ist sein Prophet" on this self-portrait of a shouting John Heartfield could easily read, "Dada is BIG (a not-so-veiled reference to German Dada giant George Grosz) and John is (his or its) prophet." German Dada Artists George Grosz and John Heartfield holding a sign that reads, "Art is dead. Long live the new machine art." The influence of the German Dada movement on Modern Art and Modern Culture is enormous. One only has to think of Picasso's Cubism or the lyrics of John Lennon. "Yellow matter custard dripping from a dead dog's eye. Corporation t-shirt, stupid bloody Tuesday, man, you should have seen them kicking Edgar Allen Poe.' Der Dada was the main publication of the Berlin Dadaists. When John Heartfield's brother, Wieland, was called back to the WW I front, the wild poet Franz Jung joined the editorial board of Neue Jugend (New Youth). Jedermann sein eigner Fussball (Everyone His Own Football), February 1919, is important because it contains the first known political photo montage.DADA ist GROSS

Click "View Page" for more on German Dada Artists such as Hannah Höch, Raoul Hausmann, George Grosz, and John Heartfield.Die Kunst ist tot

Heartfield preferred the title "Machinist" or "Engineer" to "Artist." The young Dadaist preferred to create his art in worker's overalls.

Click "View Page" for more on German Dada Artists such as George Grosz, John Heartfield Höch, and Raoul Hausmann.Berlin Dada Art Selection

Dada was born in Zürich, but it was the German Dadaists of Berlin who made the greatest impact.

John Heartfield, George Grosz, and Hannah Höch became world famous. However, only the work of Grosz and Höch grace the walls of museums such as MOMA in New York. The vast majority of Heartfield's art still resides inside the walls of the Heartfield Archiv, Akademie der Kunste, in Berlin.

German Dada lasted only four years (1916-1920). However, it burned as bright as a star and made its mark on painting, sculpture, typography, graphic design, music, and much more.

Its energy and pioneering visions have continued to influence modern artists, including musicians such as David Bowie. Bowie stated many times his admiration for Berlin Dada.

Click "View Page" to view famous pieces of Berlin Dada.Der Dada 3, 1920

The journal displayed the typography and collage experiments of John Heartfield, George Grosz, and Raoul Hausmann.

This groundbreaking catalogue was a platform for German Dadaists to articulate their political and artistic convictions.

The issues of Der Dada included wild and satirical statements. Many of these statements are signed by the Central Office of Dadaism. This indicates the German Dadaists' perception of independence from Zürich Dada.

Click "View Page" to view the pages of Der Dada 3.

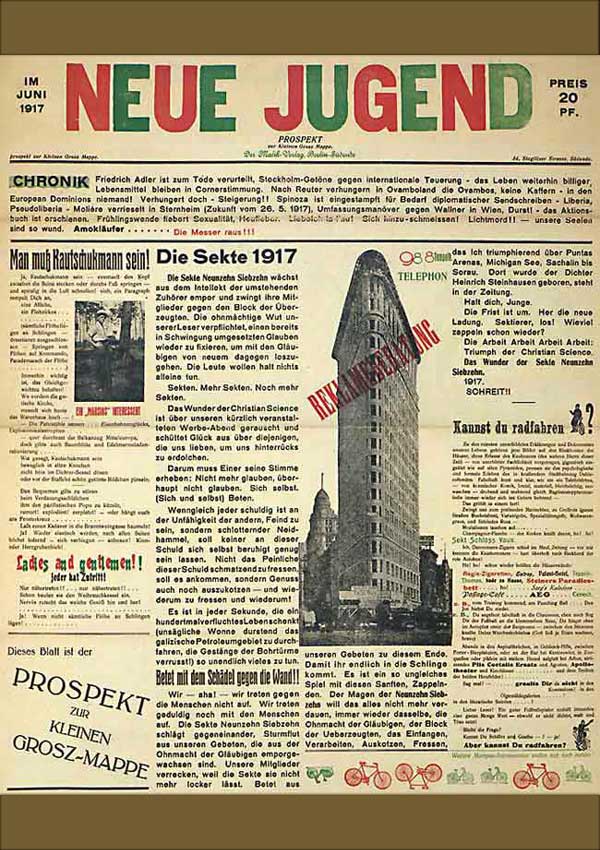

Neue Jugend, 1917

The aggressive new format of the June 1917 Neue Jugend was based on American journals.

John Heartfield developed the new style with pioneering collages and innovative typography.

Many Berliners were unnerved by art that featured coffins, crossbones, and a lady with a roguish grin. The use of these images went far beyond anything that had been seen before.

Click "View Page" to view the pages of Neue Jugend.Jedermann sein eigner Fussball

Heartfield placed well-known Weimar Republic politicians and military figures together on a fan. He scandalously asks the viewer to decide, "Who Is The Prettiest?"

Click "View Page" to view the pages of Jedermann sein eigner Fussball.

Berlin Dada. 20th Century German Dada Artists.

Berlin Dada was the center of German Dada. Dada appeared in 1916 near the start of the Weimar Republic. Berlin Dadaists produced groundbreaking and influential works. They influenced artists from Pablo Picasso (Cubism) to John Heartfield (I Am The Walrus). Art critics normally provide names for art, such as Cubism and Expressionism. The Dada movement was named by the artists themselves. Dadaists were contemptuous of art critics and what those critics considered art. The German Dada artist proudly stated, “We are Dada!”

Visit the Dada sections of the John Heartfield Exhibition. Learn about such giants as George Grosz, John Heartfield, Hannah Höch, Raoul Hausmann, Hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings, Johannes Baader, Richard Huelsenbeck, Kurt Schwitters, Hans Richter, and Max Ernst. The vision of these artists changed modern art.

Some Background

As World War I was ending, Europe was finally waking up. In Germany, as in other countries, military and political propaganda had tried to hide the horror of trench warfare and the senseless reasons for the war.

John Heartfield had his role in spreading propaganda. He was tasked with handing out leaflets that contained blatant lies. He promptly threw them all in the gutter.

The Berlin Dadaists knew what had come from old ideas and rules. They were primed to blast apart the old and create something completely new. The Berlin art scene exploded like a shell on the battlefield. Filmmakers, photographers, and writers embraced new exciting art forms. Berlin Dada painters and collage artists were at the center of the artistic cauldron that was Berlin art during the Weimar Republic.

Berlin Dadaists felt there were already too many paintings that reproduced, in some manner, what could be captured with the lens of a camera. Instead of brushes, canvases, and pots of paints, Dadaists turned to cutting up and pasting together photos from magazines and newspapers. Dada artists didn’t want to reflect reality. They want to tear reality apart. They chopped up reality with scissors and pasted it back together. The genius of George Grosz turned the rules of pencil sketches upside down. Rather than lovely sketches of models, Grosz drew his emotions directly onto paper.

George Grosz Changes Heartfield Forever

George Grosz was a eccentric genius. He was fond of white suits, heavy makeup, and pretending to someone else. At first, Berlin Dadaists thought Grosz was a Dutch businessman who had thought up twisted plans to profit from war wounded and the shrapnel that was so available in the trenches.

Grosz’s view of art had a life changing effect on John Heartfield, a young artist churning out oil paint landscapes. Heartfield burned all of his oil paintings except one, now part of the John J Heartfield collection. He would soon become a member of Berlin Club Dada and central figure in the German Dada movement. John Heartfield’s description of the birth of political photomontage (photo montage) is fascinating. It’s also almost as complex and challenging as a Dada work of art.

John Heartfield Describes The Birth Of Photo Montage

In 1967, John Heartfield, in a conversation with Bengt Dälback (Moderna Museet, Stockholm) said the following:

“[…] how I got the idea of making photo montages. I’d say [..] I started making photomontages during the First World War. There are a lot of things that got me into working with photos. The main thing is that I saw both what was being said and not being said with photos in the newspapers. The most important thing for me was that I intrinsically become involved in the opposition and worked with a medium I didn’t consider to be an artistic medium, photography. [..]

I found out how you can fool people with photos, really fool them. [..] You can lie and tell the truth by putting the wrong title or wrong captions under them, and that’s roundly what was being done. Photos of the war were being used to support the policy to hold out when the war had long since been settled on the Marne and the German army had already been beaten. [..]

I was a soldier from very early on. Then we pasted, I pasted, and quickly cut out a photo and then put one under another. Of course, that produced another counterpoint, a contradiction that expressed something different. That was the idea. It still wasn’t all that clear to me where it would lead to, or that it would lead me to photomontage.