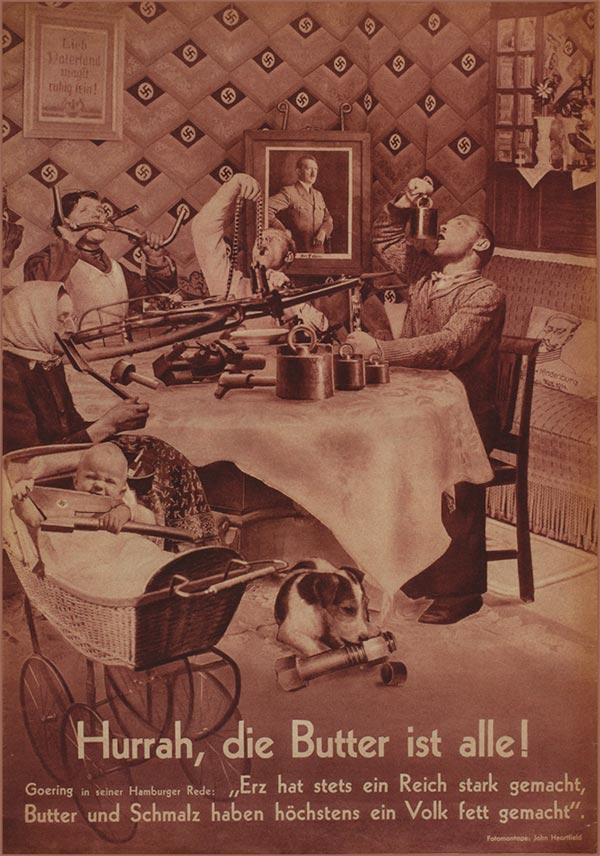

Famous Anti-Fascist Images. Hurrah, die Butter ist alle! – Hurrah, Butter Is All Gone! – Hurrah, There’s No Butter Left!

Hurrah, die Butter ist alle!(Hurrah, There’s No Butter Left!)

Hurrah, There's No Butter Left!

Hurrah, The Butter Is All Gone!

AIZ

(Arbeiter–Illustrierte–Zeitung)

December 19, 1935

Share Your Reaction To This Art

Visiting Scholar’s Commentary

War Will Never Nourish

By John J Heartfield

This complex piece is one of the most famous anti-fascist images showing the effect of senseless war on civilians. This complex piece of John Heartfield art plays off the words of a speech Hermann Goering gave in Hamburg.

The caption (Hurrah, die Butter is alle! Goering in seiner Hamburger Rede: “Erz hat stets ein Reich stark gemacht, Butter und Schmalz haben höchstens ein Volk fett gemacht.”) translates to (Hurrah, There’s No Butter Left! Goering in his Hamburg speech: “Ore [iron] has always made an empire strong, butter and lard have made a people fat at most.”). There is terrible sadness in Heartfield’s comical take on Göring words.

This famous anti-fascist image is meticulously detailed, right down to the tiny swastika on the ax the baby uses as a teething ring.

Sadly, the maquette (the original photomontage) for one of history’s most powerful works of antiwar art has been lost forever.

Hurrah, There Is No Butter Left!

A Commentary by Andrea Hofmann

Goering pointed out in his Hamburg speech that butter and lard stand for indulgence. (See text at the bottom of the poster). So John Heartfield’s message is: “From now on, you will be exposed to military propaganda in its ‘crudest’ form. It will invade every aspect of your life.”

The poster was published in 1935. That was way before the “real” war at home started. It’s a brilliant visual indictment of how war causes families to suffer while steel and munition manufacturers thrive.

However, the underlying message is more subtle than that. If you take a closer look, you can see the swastikas that are part of the wallpaper. The swastikas hint at the fact that you don’t ever know who is listening. This also means everyday products are already part and parcel of the propaganda machine. It’s possible John Heartfield was familiar with Antonio Gramsci and his theory of cultural hegemony in one way or another.

There is also a framed picture in the montage that says, “Lieb Vaterland magst ruhig sein!” This line is part of a German poem called “The Watch on the Rhine” by Maximilian Schneckenburger (1819-1849) and was set to music after his death by Carl Wilhelm. It was very popular in Germany during the Franco-Prussian war (1870-71) and World War I. The Nazis loved that song and often used it for propaganda purposes because it idealized patriotism and nationalism. The tune served as a means to boost morale and advertise perseverance. In a nutshell, this picture advertises the vital part that dominant art and design played in propaganda.

There’s a cushion displaying Hindenburg on the sofa. Hindenburg was the political leader who offered Hitler the chancellorship in 1933. He had been a national war hero and President of the German Republic prior to that. The reference links the military to the democracy of the German Republic, i.e. “war and peace.” So basically, the past influences the present and lives on into the future (represented by the baby).