John Heartfield Bio. Dadaist, Anti-Nazi Artist, Pioneering Graphic Designer, Brecht’s Stage Designer

John Heartfield Biography.

The Artist Who Fought Hitler With Scissors & Paste

This Brief Description Of The Life of the German Dada Pioneer, Groundbreaking Graphic Designer, and Anti-Fascist Collage Artist, John Heartfield, was written by his paternal grandson, John Joseph Heartfield. It has been slightly modified from the bio John J Heartfield wrote for The Encyclopedia of German-American Relations. Gratitude is owed to several John Heartfield Scholars for additional information.

For John J Heartfield’s personal recollections of his grandfather, please visit: John Heartfield’s Personal Life.

The Chronology Section offers a year-by-year account of John Heartfield’s life and times.

Bertolt Brecht: “John Heartfield is one of the most important European artists.”

John Heartfield is known:

- As the founder of modern photomontage (photo montage), a form of collage. Living in Berlin, he risked his life to use his art “as a weapon” to combat fascist propaganda, Adolf Hitler, and The Third Reich.

- As the inventor of 3-D book dust jackets, book covers that told a “story” from the front cover of the book to the back.

- For his groundbreaking use of typography as a graphic design

- For his innovative theater collaborations with Bertolt Brecht. Work that inspired the world-famous playwright and composer to develop a new form of theater.

German artist John Heartfield is a clear example of artistic genius combined with heroism going far beyond the necessary courage of any great artist.

John Heartfield Biography

John Heartfield’s Art Saved Lives

Heartfield’s anti-fascist anti-Nazi art became famous on both sides of the Atlantic before and during WW2. Heartfield used fascists’ own words and images against them. His message was clear: “You must oppose this madness, escape, or do both.”

John Heartfield Biography

The Photomontages Of The Nazi Period

A John Heartfield biography must highlight the years when Heartfield’s genius reached its zenith. His famous political art, which he labeled “photomontages” expressed his hatred of fascists, especially Adolf Hitler and The Third Reich. From 1930 to 1938, Heartfield designed 240 pieces of anti-Nazi art for the AIZ [Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung], a magazine published by the New German Press, under the direction of left-wing political activist Willi Münzenberg. The AIZ had a significant readership in Weimar-era Germany. It may easily have had the second-highest circulation in Germany in the early nineteen-thirties. After the National Socialists took control, the AIZ was smuggled into Germany from Czechoslovakia, Austria, Switzerland, and Eastern France.

To fully understand a John Heartfield biography, it’s vital to remember his artistic courage was equal to his physical courage. Heartfield was a resident of Berlin until 1933. The essential point is that his vehemently anti-fascist collages appeared on the covers of the AIZ on newsstands throughout the city. From 1930 to 1933, Heartfield’s scathing anti-Nazi montages were visible on street corners throughout Berlin. Supporters also pasted posters of his montages on walls and surfaces for any passersby to see.

Although he shined in several other mediums, such as stage sets and book covers, Heartfield is best known for the satiric political montages he created during the 1930s to expose the insanity of Adolf Hitler, Herman Göring, and the entire Nazi philosophy. To battle the Third Reich with art, Heartfield created some of his most famous montages.

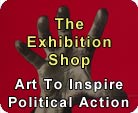

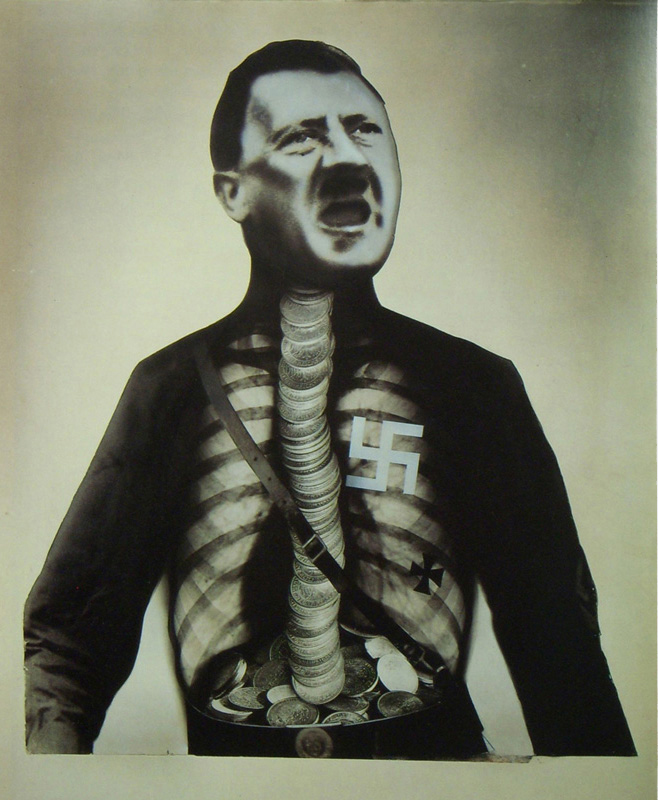

Adolf der Übermensch and Goering: der Henker are two examples of photomontages Heartfield produced and had widely distributed while he remained under constant threat of assassination by Hitler’s Third Reich.

This 1932 John Heartfield portrait of Adolf Hitler In Adolf The Superman: Swallows Gold and spouts Junk appeared in newsstands in 1932 on the cover of the popular AIZ magazine. Heartfield used an X-ray to show gold coins in the Führer’s throat leading to a pile in his stomach. Hitler changes his supporter’s gold to lies.

Adolf Der Übermensch: Schluckt Gold und redet Blech

(Adolf The Superman: Swallows Gold and spouts Junk)

In the photomontage Göring: The Executioner of the Third Reich, Hitler’s designated successor is depicted as a bloody butcher. In 1934, Heartfield created this famous AIZ cover that exposed Hermann Goering as The Third Reich’s executioner. Goering had blamed the Reichstag fire that helped Hitler seize power as the work of Jews and communists.

Göring: Der Henker des Dritten Reichs (Goering: The Executioner of the Third Reich)

AIZ Magazine Cover, Prague, Czechoslovakia, 1933

From 1930 to 1938, he created an astounding 240 photomontages for covers of the AIZ magazine (circulation around 300,000 to 500,000 at its height). These 240 brilliant works of art were a complete description of the rise of fascism in the 20th century.

Heartfield’s AIZ covers appeared on street corners all over Adolf Hitler’s Berlin. His “Photomontages of the Nazi Period” stand alone in the history of political art.

Heartfield lived in Berlin until Easter Sunday, April 1933, when he narrowly escaped assassination by the SS. He fled across the Sudeten Mountains to Czechoslovakia, where he rose to number five on the Gestapo’s most-wanted list.

Below is an excerpt From David King’s book, John Heartfield, The Devastating Power Of Laughter. It describes the 1933 Easter Sunday Evening when Hitler’s jackboots came for John Heartfield.

“Berlin, April 14, 1933: They came for him in the night. The paramilitary SS burst into the apartment block and headed straight for the raised ground floor studio where John Heartfield was in the middle of packing up his artwork, knowing that his only chance left of survival was a life in exile; he was on their most wanted list. Hearing them dislocating his heavy wooden door, he dived through his french windows and leapt over the balcony into the darkness. He landed badly and sprained his ankle.

The Nazis made a flashlight sweep search of the darkened courtyard below yet failed to focus on an old metal bin in the far corner on which were displayed some enamel signs, the sort that advertise motor oil, or soap, or an aperitif. Under its battered lid, one of Hitler’s greatest enemies, far from having vanished into the ether, crouched in torment, squashed in a box full of the local residents’ garbage. For the next seven hours he hid there, toughing it out as he heard the nightmare sounds of the barbarians ransacking his studio and destroying his work.

When the raid was over, Heartfield quietly and unobtrusively opened the lid, climbed out of the bin, exited the courtyard and began his nerve-racking flight to Prague. Germany was now enemy territory, there was a high price on his head and he had nothing.”

After his narrow escape from the SS, Heartfield walked around the Sudeten Mountains to Czechoslovakia.

[Below: John Heartfield In Mountain Gear. Credit: John J Heartfield Collection.]

Heartfield had been beaten by Hitler’s supporters and thrown from a streetcar in Berlin. The artist who openly attacked Adolf Hitler and The Nazi Party while living in Berlin was five-foot-two inches tall, with red hair and blue eyes. His “weapon” was his imagination, scissors, glue pots, dabs of paint, and stacks of photographs and magazine articles. He insisted his montages contained both literal and ethical truth.

From his early work as a fledging painter to his embrace of Dada to the anti-fascist montages that made him a Nazi target, Heartfield’s life and work was a profile in courage.

Forced to flee Nazi Germany a step ahead of the SS, Heartfield attacked the Nazi Party from Prague.

You can find more of Heartfield’s collages in ART AS A WEAPON has more of John Heartfield’s anti-fascist collages with commentaries.

John Heartfield Biography

The Frail Artist Who Stood Up To Hitler

Heartfield was born into poverty on June 19, 1891, in Berlin-Schmargendorf. He was named “Helmut Franz Josef Herzfeld.” The photo above of a young Helmut Herzfeld with a moustache was taken in 1912. Under the photo at the top of this page is a scan of what Herzfeld wrote on its back [Credit: John J Heartfield Collection].

When he was eight, Heartfield’s parents abandoned him, his younger brother, Wieland, and their two even younger sisters, Charlotte and Hertha, in a cabin in the woods. The children were separated and raised in a series of foster homes. Throughout his life, Heartfield maintained a close relationship with his brother, Wieland. In 1913, Wieland Herzfeld also changed his name, less dramatically to “Wieland Herzfelde.”

In 1916, while he was living in Berlin, Herzfeld became disgusted with the shouts of “God Punish England!” that were so common in the streets of the city. As a protest against the anti-British fervor sweeping Germany, he informally changed his name from Helmut Herzfeld to John Heartfield to become, as David King later described him, “the greatest political artist and graphic designer of the twentieth century.”

It was not until August 27, 1964, that Helmut Herzfeld was changed legally to John Heartfield.

In 1912, after studying arts and crafts in Munich and Berlin, he found work as a commercial artist. From the beginning, Heartfield was infused with a passionate belief that the purpose of art was not to glorify the artist but to serve the common good.

In 1915, Heartfield met the eccentric genius George Grosz. Shortly afterward, Heartfield destroyed all his paintings [mainly landscapes] except one entitled, The Cottage In The Woods.

Grosz had opened his eyes. Heartfield saw his oil paintings did not reflect his passion for honesty and change. He was a founding member of Berlin Club Dada in 1918 and became a central figure in the German Dada art movement. Dada has had a profound effect on culture, advertising, politics, and society. Early one morning in 1916, Heartfield and George Grosz experimented with pasting pictures together. From this exercise grew Heartfield’s lifetime obsession with “photomontage.”

In 1917, John Heartfield founded the Malik-Verlag publishing house in Berlin. At that time, his beloved brother, Wieland, was serving near the front. The brothers were soon to become partners in Malik-Verlag, with John responsible for most of the graphics..

Heartfield invented the concept of three-dimensional wrap-around book dust jackets. The book dust jackets told a story from the front cover to the back. There’s speculation that Malik-Verlag sold more publications because of Heartfield’s covers than the books’ actual content.

In 1920, Heartfield helped organize the Erste Internationale Dada-Messe [First International Dada Fair] in Berlin. Dadaists were the young lions of the German art scene, rebels who often disrupted public art gatherings and made fun of the participants. They labeled traditional art trivial and bourgeois. Heartfield was a vital member of a circle of German titans that included Hannah Höch, George Grosz, Kurt Schwitters, Richard Huelsenbeck, Raoul Hausmann, and others.

During the 1920s, Heartfield produced many photomontages for Malik-Verlag Publishing. He created groundbreaking dust jackets for books by Upton Sinclair, Kurt Tucholsky, and many other progressive writers.

In January 1918, Heartfield joined the newly founded German Communist Party (KPD). The KPD, eventually blamed by the Nazis for the burning of the Reichstag, was the only serious political threat to the rise of Adolf Hitler and The Third Reich. From many of his montages, it is clear that Heartfield blamed the greed of capitalists, especially those that manufactured steel and munitions, for the horrors he had witnessed firsthand during World War I.

It is essential to note that the vast majority of his work demonstrates that Heartfield was a devoted pacifist. CURATOR’S NOTE: My own conversations with my grandfather made it clear that he never supported violence in any form. He had faith in people and the truth. He was convinced if he brought the two together, the result would be a better life for all.

John Heartfield Biography

Artistic Genius In The Weimar Republic

The work of Weimar Republic artists, writers, composers, and playwrights had a profound effect on Heartfield. He, in turn, profoundly influenced their work. His theater sets were vital elements in the early works of Bertolt Brecht and Erwin Piscator.

The Alienation Effect [Verfremdungs-effekt]

Heartfield played a profoundly role in helping Brecht to realize the concept of the “Alienation Effect” [Verfremdungs-effekt]. The playwright used Heartfield’s simple props and stark stage sets. Heartfield’s streetcar broke down one night on the way to the theater. He had to carry his screens for an Erwin Piscator play through the streets. He arrived after the play had begun. Piscator stopped the play and asked the audience to vote on whether Heartfield should be allowed to put up his sets.

Brecht developed the technique to remind spectators that they were experiencing an enactment of reality and not reality itself. Brecht interrupted his plays at key junctures to let the audience to be part of the action and not lose themselves in it. It’s a form of theatre that continued through decades in shows such as those by The Living Theater and Joe Papp’s Shakespeare productions.

The “Engineer” Heartfield

Heartfield preferred reality to artistic pretension. While he referred to himself as a “monteur,” he preferred the title “engineer.” A George Grosz painting The Engineer Heartfield hangs in MOMA, The Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Although he did not wish to be labeled an artist, Heartfield had a full measure of an artist’s passion. His Dada contemporaries tied him to a chair and enraged him to experience the unbridled intensity of his emotions.

John Heartfield Biography

A Fighter For World Peace

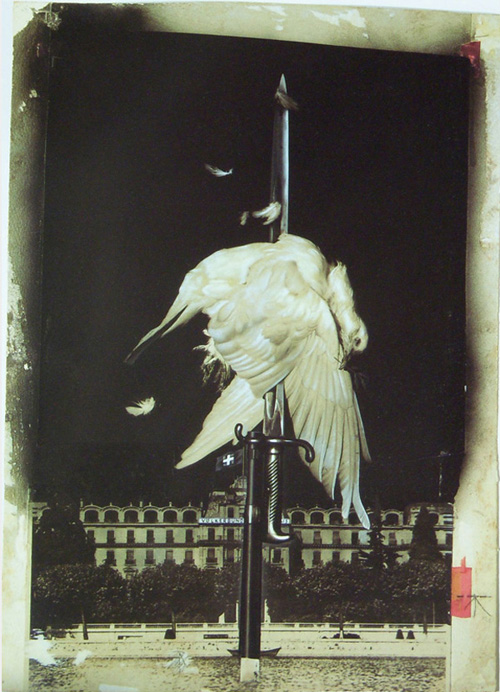

One of Heartfield’s most famous montages, The Meaning of Geneva, Where Capital Lives, There Can Be No Peace!, shows a dove of peace impaled on a blood-soaked bayonet in front of the League of Nations, where the cross of the Swiss flag has morphed into a swastika. John Heartfield loved animals and nature. This image can be considered an intensely deep emotional expression.

Der Sinn von Genf The Meaning of Geneva AIZ Cover, Berlin, Germany, 1932

You can learn more about this montage and many others, along with historical perspective, in the exhibition’s ART AS A WEAPON section.

Heartfield’s artistic output was enormous and widely displayed. Through rotogravure—an engraving process whereby pictures, designs, and words are engraved into the printing plate or printing cylinder—he was able to reach this audience he coveted.

CURATOR’S NOTE: I’m sure my grandfather would be pleased and fascinated to see his work reproduced on the Internet and this Digital Exhibition.

Forced to flee from Berlin, he continued to use the National Socialists’ own words to expose the truth behind their twisted dreams. In 1934, he montaged four bloody axes tied together to form a swastika to mock The Old Slogan in the “New” Reich: Blood and Iron (AIZ, Prague, March 8, 1934).

In 1938, he had to again run for his life before the imminent Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia. There were over 600 people on the Gestapo’s Most Wanted List, and John Heartfield was near the top. He settled in England. He was interned several times in England as an enemy alien. He was released as his health began to deteriorate. He settled in England. He was interned several times in England as an enemy alien. He was released as his health began to deteriorate. His brother, Wieland, was refused an English residency permit in 1939 and, with his family, left for the United States. John wished to accompany his brother but was he was not granted immigration status.

John Heartfield Biography

East German (GDR) Persecution

In 1941, Heartfield made it clear that he wished to remain in England and did not wish to return to East Germany [see John Heartfield Letter, 1941]. He and his third wife, Gertrud, found themselves with limited options.

Humboldt University in East Berlin offered Heartfield the position of “Professorship of Satirical Graphics” in 1947.

His response was, “Do I have to be a professor?”

Eventually, his brother Wieland convinced Heartfield to join him in East Berlin. He wanted his brother to take the apartment next to him. Because Wieland had a comfortable position at a university, Wieland believed East Germany would welcome John and treat him well.

In 1950, John Heartfield joined his brother in East Berlin. He held strong beliefs in communist ideals in his youth, but communist reality greeted him with suspicion because of the length of his stay in England. The Stasi interrogated him, and Heartfield faced a treason trial. For six years, The East German Akademie der KünsteHeartfield denied him admission, so he was not recognized for his artistic achievements and denied health benefits when he suffered health attacks.

After six years of official neglect by the East German Akademie der Künste [Academy of Arts], Bertolt Brecht and Stefan Heym intervened on Heartfield’s behalf. He was admitted to the GDR AdK in 1956. However, his health never improved. He devoted his life’s remaining years to creating brilliant sets, costumes, stage sets, and stage projections for the East German Theatre.

John Heartfield died on April 26, 1968, in East Berlin, German Democratic Republic.

Almost all of John Heartfield’s surviving original art is held within the Heartfield Archiv, Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Germany. David King donated his collection to the Tate Modern London. Hopefully, there will be free public exhibitions soon. Hopefully, there will be free public exhibitions soon.

From April 15 to July 6, 1993, the second floor of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City was the American venue for a critically acclaimed exhibit of John Heartfield’s photomontage montages.