The Political Photomontage of John Heartfield

<< HIDDEN GENIUS / Art Scholars

<< HIDDEN GENIUS / Art Scholars / Meral Bostanci

“Whoever Reads Bourgeois Newspapers Becomes Blind and Deaf”:

The Political Photomontage of John Heartfield

by Meral Bostancı, MA (Art Theory and Criticism)

The art of photomontage features the elaborate arrangement of the photographs which embody profound metaphors. Thus, the montage manifests itself as a pictorial metaphor with the entire energy and the power of the reality. The majority of the views and thoughts as to the contribution of Berlin Dada movement to the plastic arts centres mostly on the technique and the methods of the photomontage. The revolutionary applications emerging in the art of photomontage then are commemorated with the novelties identifying the high art in the Weimar Period. For instance, John Heartfield (1891-1968) introduced himself as ‘The Dadaist Photomontager’ in the First International Dada Fair which was held in 1920, and he preferred to be known as the ‘photomontager’ rather that ‘artisan’. [1]

John Heartfield, who was a peer and a sincere friend of the well-known theatre director and playwright Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956) impressed the art of photomontage radically at that period. In terms of the formal structure, the technique and the negations as well as the fighting spirit and the artistic attitude, the photomontage also held an equivalent position among the other pioneer authentic movements of art such as cubism and expressionism to arouse the world against the rise of Hitler and the Nazism. Struggled against the multidirectional propaganda of the Nazis, John Heartfield especially made visible the facade of the Nazi regime via a wide variety of arts.

From left to right: John Heartfield, “Whoever Reads Bourgeois Newspapers Becomes Blind and Deaf: Away with These Stultifying Bandages!” (Wer Bürgerblätter liest wird blind und taub. Weg mit den Verdummungsbandagen!) AIZ, no.6, 28×38 cm., 1930. [2]

The 102nd and 103rd pages of the issue of AIZ on which the photomontage titled “Whoever Reads Bourgeois Newspapers Becomes Blind and Deaf” of John Heartfield is published [3]

On the 9th of February 1930, the photomontage of John Heartfield was published full-page in the Worker’s Official Newspaper (Die Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung/AIZ). Captioned “Whoever Reads Bourgeois Newspapers Becomes Blind and Deaf!” this work of John Heartfield illustrates a head covered with two newspapers, Tempo and Vorwaerts. Both of the newspapers wrapped over the head were the press organs of Social Democratic Party of Germany. [4]

The police harness wrapping the upper body represents the collaboration between Social Democratic Party of German and the security forces of the state. The verses shown on the work is a parody of a well-known song of the German people: “Ich bin ein Preuße, kennt ihr meine Farben?” (“I am Prussian, do you recognize my colours?”) Rather than reflecting it as a public spirited occurrence, Heartfield transformed the nationalist song as such:

I am a cabbagehead, recognize my leaves?

Sorrows make me lose my mind

But I’ll stay quiet and hope for a saviour

I want to be a cabbagehead, black, red and gold [5]

Don’t want to see or hear

Stay clear of politics

And even if they strip me naked

The red press won’t come in my house!”

Resorting the material texture and the images, John Heartfield criticized anything which he interpreted as the malaise of the SPD and its embracement as the political, economic and social status quo by the community. In the photomontage, the signified is a German stereotype who buries his head in the sand, and the literal meaning here is that the mind is exposed to the SPD rhetoric. There is a mental imprisonment which impedes the mobilization to act. Not only the Social Democratic Party is accused of supporting the bourgeois state, and opposing the Communist Party by amounting the reactionary politics, but also the SDP threatens with a political blindness which both deafen and blind its readers. In consequence, it eliminates the actions and the opposition. [6]

The montage, shown on the 103th page of AIZ, was published with an article in the previous page. The purpose of this apparition is to demonstrate the audience how the photographs in other newspapers are manipulated for various reasons. We can see how the skirt of a painter is lengthened in a periodical as she poses with her painting of the pope. [7]

AIZ manipulated this image to illustrate a story which was actually based on the deceptive practices of the Catholic religion and the bourgeois press. In the first page, there are two photographs, one of which illustrates the straight one, the other retouched. Keimer- Dinkelbühler, a German woman painter, who is appointed to paint the Pope’s portrait, is sitting in front of her easel at the Vatican. The fact that the painter’s skirt is lengthened by the bourgeois press to cover her legs is stated at the bottom of the photograph. According to Maud Lavin, the issue is as such:

“…if such an image can be falsified, no photography, thus no truth, is free from manipulation. Regarding the two photos, on the second page, there is the full page anonymous Cabbagehead of Heartfield which is sandwiched within the newspapers. Using these mainstream socialist newspapers, Heartfield’s real purpose is to ridicule the opposition and its manipulation of reality. Heartfield has explicitly staged a story in his photograph though the reality may be admitted only at a certain point. [8]”

Sabine Kriebel explains that John Heartfield’s photomontage “Whoever Reads Bourgeois Newspapers Becomes Blind and Deaf: Away with These Stultifying Bandages!” presents how the political aesthetics of the image should be interpreted.

“The discourse of Whoever Reads Bourgeois Newspapers Becomes Blind and Deaf! investigates all sorts of concealment of production. In this photograph, a Cabbagehead mummified with the scraps of newspapers, directs the viewers the question of “I am a Cabbagehead, recognize my leaves?” by the help of a footnote at the right corner of it. Due to the newspapers covering the eyes, the mouth and the head, the man is deafened and silenced. He can see or speak no longer. Even, according to the caption printed in black and thick letters, “Whoever Reads Bourgeois Newspapers Becomes Blind and Deaf”, he can’t hear. The mainstream newspaper of Social Democratic Party, Vorwaerts and a popular socialist newspaper Tempo, thus addresses to the press of the bourgeoisie. The image not only arouses a feeling of violence achieved by the cut-and-paste technique, but also it represents a psychological disturbance created by a realistic presentation.

The invisible facet of Cabbagehead is a photograph that reveals the picture’s seamless illusionism, weaving us into its delusionary extension of reality and that is scrutinized by the reader in the same way. The person looking at AIZ recognizes the Cabbagehead as the antithesis of himself/herself; the Cabbagehead is identified as someone who is labelled as a socialist because of the uniform he wears and the newspaper he reads, however he is someone against the communism. The photograph makes a verbal-visual pun with the word ‘Blaetter’ which means a letter of cabbage: The nationalist Prussian song, “Ich bin ein Preusse, kennt ihr meine Farben?” (“I am Prussian, do you know my colours?”), is transformed into a political indictment of the socialist picture press. The language creates a visual continuity between the text and the photograph rather than addressing the senses. The purpose, here, is to impress the audience with a cautionary story: It implies if you read a socialist media press, you will become blind; however if the newspaper AIZ, in which you encounter with the Cabbagehead, opens your eyes and your ears to discern the political reality and frees your mouths to speak. The photomontage discusses the ideological subjectivity created by the press via an implicit dialectic founded between the suffocating mental imprisonment of the socialist illustrated media and the power bestowed by AIZ. The montage attempts to introduce a new communist subject as a participant to deconstruct the meaning by creating an antithesis of the passive Cabbagehead socialist. The photomontage of John Heartfield leads the reader to analyse the shifts between the image and the material texture as well as the explicit and implicit meanings, and also to find a path between the politic parody and the visual plays. Our seeing face confronts with the blind counter portrait, mystifying and disturbing impotency of ours.”

The photomontages of John Heartfield in AIZ not only aim to address the audience visually, but also to prompt them to action with the psychological impression they incur. Rather than only creating a temporary ‘shock’ effect of Dada montage on the audience by compelling them psychologically, they embark a smart and subtle understanding. Through the photographic illusion, the photomontage means to tempt the audience, immerse the beholder and capture him/her very tightly. Here it is not the cautious bourgeoisie who is under attack, but the AIZ readership who is to be critically provoked and engaged. At the same time, we are in the territory of agitation propaganda agitation office which mobilize and educate the readers ideologically. [9]

From left to right: Semen Friylyand, “The face of the Bourgeous Press”,1951. [10]

John Heartfield, “Brotherly Greetings from SPD “, 1931, AIZ. [11]

In his AIZ work, Heartfield makes ridicule with the dedication of the community to the manipulations of the general press of the bourgeoisie, and moreover he criticizes the unquestioning readership. By illustrating an effigy of a man in his working costume and wrapped by the wires, and his head covered completely by the newspapers, John Heartfield means to captivate and stir the audience with the help of the caption “Whoever Reads Bourgeois Newspapers Becomes Blind and Deaf!” printed under this depressing photograph. This montage of John Heartfield represents an extraordinary subtle stage; however, it is rendered in an unconventional way being predominantly based on the similar or the same materials pressed beforehand. [12]

Exposing the blind people with various themes related to the animalistic and the cruelty of the war had become the profound way to express oneself in those years. Although John Heartfield is identified to be far from this politic attitude, he has contributed to the figurative works of that period. [13]

From left to right: Honoré Daumier, M. Chevassut. “Last Shareholder of the Constitution” (Dernier actionnaire du Constitutionnel), 1st Febryary, 1834, Le Charivari. 26,7 x 18,2 cm gravur.[14]

Honoré Daumier, “Will There Be The Eclipse?” (L’éclipse sera-t-elle totale?), 17th, January 1871, Le Charivari. 23,7 x 19 cm Lithography. [15]

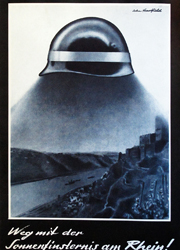

John Heartfield, “Away With the Eclipse of the Sun on the Rhein!”(Weg mit der Sonnenfinsternis am Rhein!) [16]

According to Franck Knoery, most of the photomontages of John Heartfield have been directly inspired of the caricatures of Honoré Daumier (1808-1879) drawn for the newspapers Le Charivari and La Caricature. The bourgeoisie whose head is sandwiched between the reactionist press is deafened and made blind may be an excerpt of gravure representing “Last Shareholder of the Constitution” (Dernier actionnaire du Constitutionnel) which was printed in Le Charivari on the 1st of February, 1834. Similarly, the montage he arranged in concern with the untimely recession of the allies and a Prussian casque which overshadows the sun in the Rhein Valley makes a reference to a work of lithograph composed in 1871. In this work, the Prussian casque leaves the whole Europe under its shadow by covering the sun of liberty. Consequently, as remarked by Franck Knoery “Different samples covering the imitation and quotations can be multiplied as well as the other works composed by various graphic methods”.[17]

The politic photomontage, pioneered by John Heartfield, has been one of the most interesting artistic technique in the 20th century. There are some leading artists in this domain. Kaethe Kollwitz (1867-1945), George Grosz (1893-1959), Rudolf Schlichter (1890-1955), Alexandr Rodçenko (1891-1956), László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946), El-Lissitzki (1890-1941), Gustav Klutsis (1895-1938), Herbert Bayer (1900-1985), Gottfried Kirchbach (1888-1842), Otto Baumberger (1889-1961), Mihaly Biro (1886-1949) and Willibald Krain (1886-1945) are some of them. On the other hand, presently we can observe that there are contemporary artists producing these kind of works. [18]

However, there is a subtle distinction between the works of John Heartfield and the works of so-called “the political art” exhibited today in the museums or the biennials: While this type of politic art expresses the political position of its creators, it doesn’t sincerely aim to change the realpolitik through the arts. Arthur C. Danto (1924) states that the reason lying behind this fact is that the concept of museum is assumed to be the primary territory the art can be realized; thus, the aesthetic appreciation is the only means to demonstrate the impact of the arts. However, it should be accepted that the visitors of the museum are made the sole and the primary addressee because nobody will ever see this work. Along with that, the visitors of the museum typically are inclined to adopt the attitude and the values of the artists. According to Arthur C. Danto, the politic art should not only make visible the view of the artist: “Having a serious bother with the politics means to worry about the political change sincerely and this would be the initial step to take the art out from the museum and make it engaged with our daily lives.” Of course, there were times that John Heartfield humiliated the AIZ readership to lead them to vote for a specific party or to protest the events in Germany. Accordingly he also revealed both his and his readers’ views at some extent. Consequently he became the interpreter of his audience and opposed the extremely powerful enemies through the power of art and used it to disgrace them. As all the major controversialist artists, John Heartfield accepts that the art should be socialized to be politically powerful; and for that purpose, the museums are falsified places. Rather than producing unique art works for the museums and the collectors, John Heartfield dreamed the art to be accessible in every corner only for a few penny. On other respects, according to Arthur C. Danto, we can dwell more on the graphics creativity and aesthetic purposes of John Heartfield. Moreover, though the objects manipulated for a violent attack are not the issue of an artistic discussion today, it is striking to observe how the works of art survive artistically. [19]

John Heartfield had never intended to win a name for itself. His real purpose was to warn the community against the Nazis who threatened the social justice and the human rights. Although the agents and the territory have changed, the misdeeds which were referred by John Heartfield, the militarism, war usury, genocide and holocaust, political corruption and conspiracies still persist today.

References:

[1] A. C. Danto, “John Heartfield and Montage”, The Madonna of the Future, Essays In A Pluralistic Art World, p. 5, 2001, University of California Press Ltd.: London. [ 3-10] Citation: http://books.google.com.tr/books?id=VHHizA7ZW0cC&printsec=frontcover&hl=tr&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false, The date accessed: 21/03/2013.

[2] Source: Perez, C. “John Heartfield Dada, caricature politique et lutte des classes”, John Heartfield Photomontages Politiques 1930 – 1939, p. 22, Catalogue de l’exposition (7th April – 23rd July, 2006). Musee d’Art moderne et contemporain de Strasbourg: Paris. [13-22]

[3] Source: http://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/heartfield/whoever_reads_fullpg_zm.html, The date accessed: 20/03/2012.

[4] D. Kahn, John Heartfield, Art and Mass Media, 1985, p. 73, Tanam Press: New York.

[5] With the mentioned colours here black, red and golden, he refers to the national flag of the Weimar Republic (1919-1933).

[6] C. Kay, “Art and Politics in Interwar Germany. The Photomontages of John Heartfield”, Left History. An Interdisciplinary Journal of Historical Inquiry and Debate, Vol 4, No 2, p. 32, 1996. [11-50] Citation: http://pi.library.yorku.ca/ojs/index.php/lh/article/view/6982/6166, The date accessed: 21/03/2013.

[7] See. http://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/heartfield/whoever_reads.html, The date accessed: 21/03/2013.

[8] M.Lavin, “Heartfield in Context”, Art in America, p. 89, 1985 [85-93] Citation: http://www.johnheartfield.com/HEARTFIELD-ART-CONTEXT/john_heartfield_ART_CONTEXT_01.html, The date accessed: 22/03/2013.

[9] S. Kriebel, “Manufacturing Discontent: John Heartfield’s Mass Medium”, New German Critique 107, Vol.36, No. 2, p. 62-65, 2009. [53-88] Citation: http://cora.ucc.ie/bitstream/10468/215/1/Kriebel_HeartieldSuture.pdf, The date accessed: 20/03/2013.

[10] Source: P. Pachnicke, K. Honnef, John Heartfield, 1992, p. 277, Harry N. Abrams Inc: New York.

[11] Source: P. Pachnicke, K. Honnef, op. cit., p. 192,

[12] S. Taylor, “Heartfield’s Photo-Grenades”, Art in America, June – July 2006, p. 158, Brand Art Publications Inc: Broadway, New York. [156-162]

[13] E. Siepmann, John Heartfield, 1978, p. 27, Foro Buonoparte: Milano.

[14] Source: F. Knoery, “John Heartfield: l’oeuvre opératoire”, John Heartfield Photomontages Politiques 1930 – 1939, p. 34, Catalogue de l’exposition (7th April – 23rd July, 2006). Musee d’Art moderne et contemporain de Strasbourg: Paris. [33 – 41]

[15] Source: F. Knoery, “John Heartfield: l’oeuvre opératoire”, John Heartfield Photomontages Politiques 1930 – 1939, p. 35, Catalogue de l’exposition (7th April – 23rd July, 2006). Musee d’Art moderne et contemporain de Strasbourg: Paris. [33 – 41]

[16] Source: W. Herzfelde, John Heartfield, Leben und Verk, 1971, p. 234, Auflage VEB Verlag Der Kunts: Dresden.

[17] F. Knoery, “John Heartfield: l’oeuvre opératoire”, John Heartfield Photomontages Politiques 1930- 1939, p. 35, Catalogue de l’exposition (7th April – 23rd July, 2006). Musee d’Art moderne et contemporain de Strasbourg: Paris. [33 – 41]

[18] M. Bostancı, John Heartfield and The Interpretation of The Object, p. 386, Unpublished Postgraduate Thesis, 2012, Işık University SBE, İstanbul.

[19] A. C. Danto, Op. cit., p. 7-8.